EXPANDING PERSPECTIVES: Collecting and representing neurodiverse artists

letter from the Executive Director, Merrilee Challiss —

Recently, several social media posts came to my attention sharing news of acquisitions of artworks by neurodiverse and developmentally disabled artists by both the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) and the Oakland Museum of California (OMCA).

The acquisitions represent an overdue acknowledgement of marginalized voices according to a joint statement issued from Creative Growth, Creativity Explored and NIAD. OMCA curator Carin Adams, co-curator of the exhibition “Into the Brightness: Artists from Creativity Explored, Creative Growth & NIAD” centers the notion that “art is a fundamental human practice and form of communication that all people are entitled to.”

To read more about the exhibition:

In a statement, Director Emeritus at Creative Growth Art Center, Tom di Maria hailed the acquisition and collaboration with SFMOMA as a move that

‘further diversifies the museum’s collection to include more than 100 works by marginalized Bay Area artists,” and one that “builds critical bridges between different communities of artists, disability activists, and cultural leaders and viewers, strengthening the artistic landscape of the Bay Area.”

Like Creative Growth, Creativity Explored, and NIAD, Studio By The Tracks, though a much smaller organization, has a very similar mission — providing space, materials and facilitation for (in our case) the neurodiverse, autistic community in Birmingham, Alabama. Like our much bigger “progressive art studio” sisters in the Bay Area, we also aim to bridge the gap between the artist and the art world, acting as agents and advocates on their behalf.

All of this got me thinking about how Studio By The Tracks, celebrating our 35th anniversary this year, can play a role in expanding the definition of what art is and what our role is in terms of elevating the acceptance and awareness around neurodiverse art and artists in our own community and, finally, what role institutions and collectors play in the inclusion of diverse voices and perspectives.

So I reached out to local luminary and multi-hyphenate, John Fields — curator / artist / musician / podcast co-host of No Bad Art, and Senior Director of Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (not to mention partner to SBTT’s own talented artist and Administrative Assistant, Jennifer Fields). I really appreciate John’s nuanced perspective on what this moment means and for his thoughts on what inclusive curation looks like.

1. What are your thoughts on the recent acquisitions by institutions of works by artists with developmental disabilities? Does this represent a reckoning, a trend, a sea-change by institutions and galleries? Do you think other institutions will follow suit?

JF: This move aligns with the growing interest in promoting inclusivity and diversity within museum collections. While it is unclear whether this trend is being adopted by all institutions and galleries, it does indicate a growing awareness of the importance of showcasing the work of artists with developmental disabilities. Interestingly, commercial galleries have traditionally been more proactive in recognizing "outsider" artists, many of whom would be classified as neurodivergent today. Museums seem to be playing a bit of “catch-up” in some ways. More and more institutions will likely recognize the value of incorporating artworks by neurodivergent artists into their collections as our cultural understanding of neurodiversity evolves. Historically, individuals with developmental disorders may have been marginalized or stigmatized, and their artistic abilities may have been underestimated or overlooked. However, there has been a corresponding shift in perceptions toward acknowledging the strengths and talents of individuals, including their artistic abilities.

2. What does inclusive curation look like?

JF: Interpreting a work of art is a highly personal experience, and it is widely recognized that artistic interpretation is greatly dictated by the viewer's own personal life experience. This is why inclusivity in art museums is of utmost importance. Inclusive curation means intentionally considering diverse viewpoints, experiences, and voices when selecting artworks for exhibitions and collections. It involves actively seeking out and showcasing the work of underrepresented artists, including neurodivergent individuals. Inclusive curation also entails offering accessible interpretation and programming to ensure that all visitors feel welcome and engaged. The goal is to create a space where everyone can see themselves reflected and find connections in the art on display, regardless of their background or ability.

3. Why should art collectors include art by neurodiverse artists in their collections?

JF: Art collectors should consider including art by neurodiverse artists in their collections for several reasons, and many have done so, particularly the early collectors of vernacular art. Firstly, this will broaden the scope and diversity of their collection, enriching it with unique perspectives and styles. Secondly, it will provide support for the artistic endeavors of neurodivergent individuals, validating and recognizing their talents. Additionally, collecting art by neurodiverse artists can be personally rewarding for collectors, as they discover new and innovative works that challenge traditional notions of art. Overall, the inclusion of art by neurodiverse artists in collections contributes to a more inclusive and representative art world.

4. Do you have any favorite neurodiverse artists?

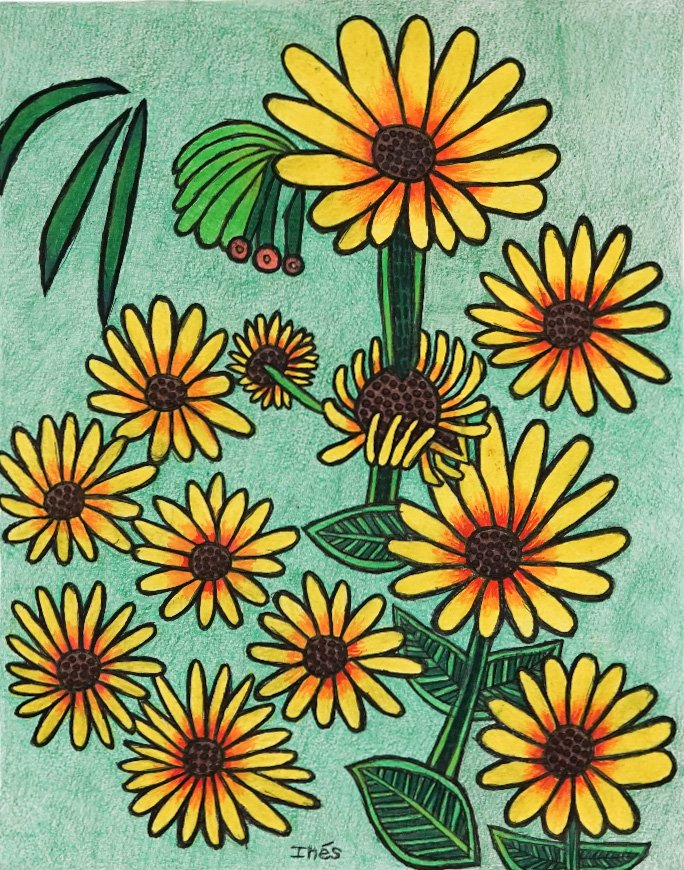

JF: I find it interesting to consider the prevalence of neurodiversity, which has become increasingly apparent in our culture. I wonder how many past stereotypes and tropes of the 'eccentric artist' were actually cases of neurodiversity? Over the years, AEIVA has showcased numerous artists who have been diagnosed, both officially and unofficially ND. Currently, we have an exhibition of Andy Warhol's work on display at AEIVA. Although he was never officially diagnosed, it is widely believed that he was neurodivergent. I think Warhol is my immediate choice. However, I’ll never forget the first time I saw Stephen Wiltshire creating an architectural cityscape from memory, and honestly, the first time I ever saw one of Inés’ paintings at Studio by the Tracks.

“An Armadillo” by Inés Oreheula, a Studio by the Tracks artist

colored pencil & ballpoint pen on paper

5. What role do institutions have to play in the acceptance and validation of neurodiverse artistic perspectives? Are there plans to include neuro-diverse artists in future exhibitions?

JF: Museums and galleries play a significant role in promoting the acceptance and validation of diverse artistic perspectives. They provide a unique space in our culture where people can explore new ideas that are not generated by algorithms designed to reinforce pre-existing beliefs. By actively featuring artworks created by neurodivergent artists in their exhibitions and collections, institutions help challenge stereotypes and promote greater understanding and appreciation of neurodiversity. Plans to include neurodiverse artists in future exhibitions can ensure that their voices are heard and their contributions are celebrated within the cultural landscape. Locally, professor and gallery director Lauren Frances Evans at Samford is already centering neurodivergent narratives and artists into her curatorial projects. (You can read Merrilee’s chat with Lauren Frances Evans here.)

For those interested in collecting work by our neurodiverse artists on the autism spectrum, please check out Studio By The Tracks’ upcoming exhibition at the Gadsden Museum of Art, opening April 5th during Autism Awareness month. As part of its 35th year celebration, SBTT will also be featured in the Cultural District as part of this year’s Magic City Art Connection at Sloss Furnaces, April 26-28th.